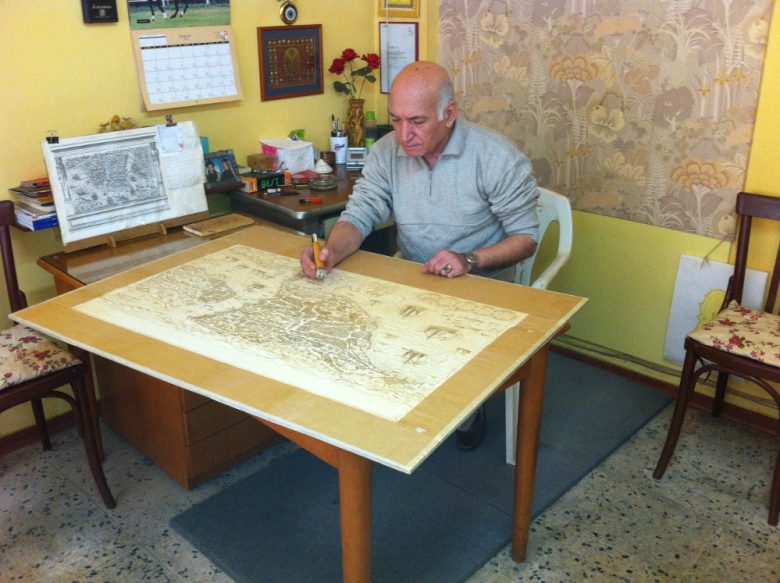

Selahattin Olceroglu is working on an ambitious project. Several years ago the retired Turkish industrial designer and interior architect set himself the task of recreating 20 Old Istanbul engravings in pyrography. “When the collection will be completed, it will be a unique and very impressive pyrographic collection to challenge with the other painting techniques in the field of visual arts,” he says. “It will be displayed as a permanent exhibition in an art museum as well as a travelling exhibition set to be exposed in the other countries when required. So, this collection will be viewed by many art lovers in the future for years, and it will introduce the art of pyrography to the art world in a very effective and striking way. It will be the best reward for me when I see my collection leads and encourages many young artists to apply the art of pyrography.”

The poplar plywood panels Selahattin is working on are large—many of them are nearly three feet wide—and it takes him many months of painstaking work to finish each one. However, Selahattin has been convinced since he was a young man that, “When a wooden panel is burnt in required medium tones correctly and successfully, it is possible to get a very attractive and impressive art work. Years ago, I thought that color tones of burnt wood would work perfectly to create the atmosphere of historical mosques, churches, fountains, and monuments as well as those beautiful engravings of Old Istanbul.” That belief is what initially drew him to pyrography and what keeps him working.

Selahattin has been fascinated by pyrography since he was 13 years old and saw a woodburned work at an art exhibit; he made his first burning at age 19. Since then, he has developed a style that he calls “painterly” because he follows many of the rules of traditional painting. For example, Selahattin specifies that the “canvas”—his plywood panels—should be a regular shape, like rectangular or square; the entire surface should be covered with pyrography, as it would be with paint; shapes should be depicted by shading rather than sharp outlines, and the shading should flow smoothly; and works should be original. Acknowledging that he breaks his own last rule by recreating ancient art, he says briskly, “I will just remind you of an old Turkish saying: ‘Do what your master tells you, don’t do what he does!’”

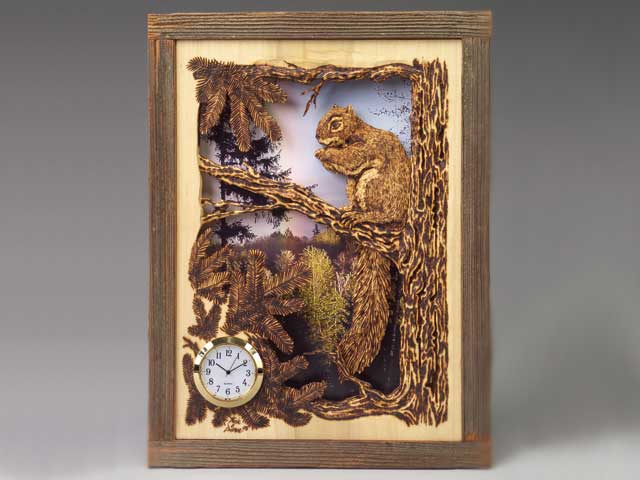

The artist further notes that these characteristics of painterly pyrography can be adjusted “when making pyrographic artworks in accordance with the procedures of other art styles, like contemporary style, surrealist style, etc. For instance, it may not be necessary to burn the full surface of the panel. There may be unburned/blank portions (gaps) between the objects or figures. Monochrome burning can be done instead of burning the wood in medium tones. The artist can utilize even the ‘meaningful’ grains on the wood panel as a part, as an object of his main theme with or without burning and toning on or around them.

“The most important thing to be taken into consideration when applying all of these variations–differently from the characteristics of realistic style pyrography–is the [importance] of capturing painterly effect.” The goal, according to Selahattin, is to follow the rules of fine art so that those who categorize such things will consider pyrographic works as visual art rather than decorative craft. “We need many more gifted artists in this field for the recognition of the visual art pyrography. We need their participation and solidarity for challenging with the other painting techniques in the field of visual arts,” he explains.

While many artists and enthusiasts are embracing the addition of color—in the form of paint, colored pencil, and other media—to pyrography, Selahattin prefers the sepia tones of traditional burned wood. He uses an adjustable-temperature wire-tip pen for part of his work, but relies on an old soldering iron with a modified copper tip for the majority of his toning and shading. Selahattin has been using the same tool since 1965, adjusting the tip in and out to change the heat and thus the color it produces. He doesn’t recommend it as a tool to other pyrographers, nothing that adjusting the bar is difficult and the tool is cumbersome, but Selahattin has been using it for so long that he’s used to it. “I am very accustomed to use this tool and I don’t ever think to replace it with any of today’s modern toning and shading devices.”

When he finishes the engravings project, Selahattin plans to turn his burner to creating realistic still lifes of old weapons. He also intends to try some contemporary-style images. Finally, the master will be following his own advice.

To see more of Selahattin Olceroglu’s work, visit his website, www.yakmaresim.com. For further details about his work, read Kathleen Menendez’s excellent article about Selahattin.

1. Coffee House in Old Istanbul. Pyrography on poplar plywood after an engraving of 19th Century British artist Thomas Allom. 2008. 32 by 45 inches.

2. Turkish Bath Cooling Section. Pyrography on poplar plywood after an engraving of 19th Century British artist Thomas Allom. 1997. 24 by 36 inches.

3. Weapon Trader. Pyrography on poplar plywood after an oil painting of 19th Century Turkish artist Osman Hamdi Bey. 2009. 18 by 24 inches